Tarr Black: Understanding Finality in The Turin Horse

by Travis Jeppesen on August 18, 2012

The adjective “apocalyptic” – and, even worse, “post-apocalyptic” – tends to suffer overuse from lazy journalists and deadline critics whose surface-glazing is rarely burdened with the task of accurately translating what’s happening before them into the medium to which they’ve dedicated themselves. Banal summarization followed by a brief compilation of superficial observations – often encoded in jargon – lend a pseudo-authoritative air to the critical task. This is one of the dangers of criticism’s increasing turn away from language-as-worldview, its diminution from artform to “service.” Buzz and cliché allegedly suffice when faced with a certain intellectual lethargy, a poverty of expression. Not only does a film like Turin Horse deserve better – it has a lot to say about the conditions that have dragged criticism, along with all the other arts, down to this degraded level.

Of course, you’re more likely to have heard about The Turin Horse than to have seen it. Nowadays, we normally prefer the background story to the messy task of engagement: The Turin Horse is to be Bela Tarr’s (gasp!) final film. After a career stretching back to 1977 and spanning only nine feature-length films, the great auteur has announced that he has nothing left to say. The finality embedded in this news story is significant, but not in and of itself; it is only significant in relation to what his final statement, The Turin Horse, imparts.

Unlike the melody sung by the critical chorus, The Turin Horse is not about the end of the world. It could be that Tarr’s film was overshadowed by Lars von Trier’s Melancholia. Connoisseurs and critics look at the three major European festivals for signs and symptoms of the Zeitgeist, and 2011 was momentous at each for unveiling a major work by three of the continent’s most iconic — when not iconoclastic — auteurs: Berlin had Tarr’s horse, Cannes presented von Trier’s apocalypse, and Venice gave us Aleksandr Sokurov’s Faust. Beyond winning awards, both Tarr and von Trier managed to stir controversy at the Festivals — Tarr with his retirement announcement, but also his subsequent alleged criticism of the Hungarian government, which led to a delay of the film’s release in his home country; and von Trier’s provocative Nazi-sympathizing jokes at his press conference at Cannes. Both feats arguably brought more publicity to the films than they would have received otherwise. And, considering that von Trier’s film is more readily digestible than Tarr’s, it’s not inconceivable that some overlap spurred the confused critical reception of the latter film.

But if anything, The Turin Horse was the anti-Melancholia. Tarr would never do something so elaborate and overstated as Lars von Trier. As is nearly always the case, von Trier’s film showcased that director’s compulsion to make a sweeping, melodramatic gestural statement, a bizarre therapeutic exhibitionism of his own private neuroses. Tarr’s film, on the other hand, is his most simplistic and straightforward to date. Von Trier is disaffected; Tarr is unaffected.

Tarr’s film clearly expresses what the real tragedy is: that the world has not ended and will not end. The world is infinite. But greatness is not. The Turin Horse implies that to live in a world without great cinema, great art — a world, in short, devoid of humanity — is to not live at all, but to dwell onwards in a state of inner deadness. In such a state, the apocalypse would come as a relief.

To understand The Turin Horse, I must try to write through The Turin Horse, or, perhaps more aptly, within The Turin Horse, to enter into that space that is marked by Tarr and yet is no longer his sole domain as he has offered it up, his vision, to anyone willing to submit to the suspension of real time and alienation of real space that entering into the cinematic scenario entails.

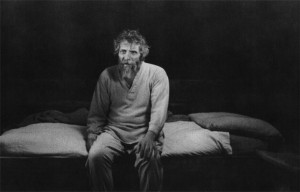

As is usual with Tarr – at least since 1988’s Kárhozat (Damnation), which marked the first film in his second and final stylistic phase that his name has become synonymous with – the premise is deliberately simple. For all the treacherous hubbub about the supposed “difficulty” of Tarr’s films, he is actually something of a minimalist. I say “something,” because his is not the classical, capitalized form of Minimalism we tend to think of when we hear the word spoken — that minimalism has been so usurped into the culture that it is well and large a part of the highest echelons of that industry: an oppositional austerity subsumed into a design principle that signifies wealth and opulence. Tarr’s minimalism is rooted in poverty, one of the central recurring subjects in Tarr’s oeuvre ever since his first feature, Családi t?zfészek (Family Nest). For Tarr, poverty is of course a social concern, yet, working as he is within the European auteur tradition — a tradition that links film with philosophy, literature, painting, and sculpture — poverty is above all constantly (re-)considered as a spiritual condition. In short, that conditionality, its eternal variations, has always been Tarr’s big theme.

The difficulty of Tarr’s films, I suppose, is that the plots are so simple, so little happens within the long extended shots, that they require an incredibly active mind if one is to admire them beyond the surface beauty and ponder the hidden and dire complexities that they probe. His films are minimal because they show a minimal form of existence, one that is marked by mere subsistence and little in the way of pleasure besides the temporary relief that drink can provide.

The film begins after Nietzsche.

“In Turin on 3rd January, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway of number six, Via Carlo Albert. Not far from him, the driver of a handsome cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and puts an end to the brutal scene, throwing his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words, and lives for another ten years, silent and demented, cared for by his mother and sisters. We do not know what happened to the horse.”

Although the event occurred in the city of Turin, the film is not set in the city. For Tarr, it is never the city – a visitor will later ask the cabman why he doesn’t go into town, to which he will reply: “The wind has blown it away” – but a rural outside, a desolate place where gale winds blow constantly, where there is little else besides the stone house where the cabman and his daughter live and the barn next door where the horse is stalled. Outside, a hilled horizon marked by a single tree, and a well a few paces from the house.

The film is divided into six days.

Day one, the cabman returns home with his horse. His daughter emerges from the house and helps him put the ailing creature away in the barn. Inside the house, the daughter undresses her father. She then prepares the daily meal as he rests.

The girl stares out the window for a long time as the potatoes boil in a pot. Shot from behind, we are unable to examine the exact nature of her seeing, but we can surmise, from the context, that it is a sort of blind staring-out at the horizon’s lack, a resignedness beyond wonder at the ferocity of the gales that have nothing to blow but dust into shapeless whirls. A few minutes later, she returns to stand over his bed. “It’s ready,” she says. It’s the first word that’s been spoken so far in the film.

What follows is the first of four studied scenes of the two eating. Each day, at the same time, father and daughter each eat a single boiled potato – nothing more. The intensive study of this simple act of consumption is one of the symbolic highpoints of the film. By this time, the viewer is well acquainted with Tarr’s style — the extended length of the shots — which, again, may account for the alleged difficulty of the director’s vision. In the dominant Hollywood cinema, the average shot length is around 3.5 seconds; Tarr’s shots can last up to eleven minutes, or more. Famously, his version of Macbeth, filmed for Hungarian television, consisted of just two shots: the first five minutes in length, the second lasting all of sixty-seven minutes. Within the confines of narrative cinema, Tarr is perhaps the most anti-Hollywood director still breathing. The problems we encounter with the temporality of his films reveal our own positions as victims of a fascistic, totalizing culture industry. In watching his films, we re-learn what it means to look.

The father briskly peels the potato with his left hand, his right arm out of use owing to some ancient injury. He eats fast and furiously, but without passion. He just wants to get it over with. When he finishes, his daughter is still picking at hers, and so now it is his turn to get up and remove himself to the window where he can observe the wind’s empty promises. In the foreground, the daughter eats much slower, but also dispassionately – so much so that she doesn’t bother to finish her potato, but scrapes away the remains into a rubbish bin.

One can live on very little, yet still manage to go on existing. This, however, is not really living, Tarr implies. The stark black-and-white photography serves to accentuate the brutalitarianism of Tarr’s vision. It is all contrasts in Tarr’s black world – these contrasts help us see the world clearer. You get the feeling that there is not a lot of color in anything he chooses to photograph anyway.

Second day. Daughter wakes up, go to the well, fetches two pails of water. Inside, she dresses her father. Father takes two shots of palinka, a strong fruit brandy made in the Carpathians. Daughter takes one shot. This, and the potato, is what gets them through the day.

They go outside to the barn. Struggle through the wind to remove the wagon. Saddle up the horse. Horse won’t move. The cabman whips the horse hysterically, but to no avail.

They did not create the horse. But they need her to survive.

The daughter emerges from the barn. “Can’t you see she won’t move?” she cries out to the old man. “Stop it!”

Daughter begins to unsaddle the horse. Father has no choice but to go along with it. The horse is taken back inside the barn, while the humans remove themselves to their holding place.

In black-and-white, nothing has value. Everything just is. The daughter is not a good or bad daughter. The father is not a good or bad father. They play the simple roles that life, the cinema, has assigned them, go through the few motions that the day has in store.

The horse is ailing. She is losing her function.

Film, as a material and a physical process, is becoming obsolete, we all know; it will die one day soon. Let us stop to review the elements at this point. We have the long, extended takes, altering the temporal aspects of our perception; we have the two characters; the third character of the wind, and the music, and more of both of these below; we have the horse, rarely seen, its titular presence nonetheless overshadowing all images we do take in. All vital signs — no apocalypse so far! — and yet through them, we intuit an enunciation of Tarr’s oppositionality. Tarr is just as political as, say, Jean-Luc Godard; Tarr’s politics are always embedded within his style. It is no accident that Tarr’s two stylistic phases coincided with two regimes: under communism, he turned Social Realism around to critique the very system that that rigidly codified style was meant to promote through his chatty, Cassavetes-esque dramas, while under the totalitarian dictates of free market capitalism, his cinema shifts into second gear, traversing those terrains we are meant to want to look away from at a painstakingly slow pace.

Father chops wood with his one good arm. Chops with the same brute bluntness that he whips the horse with, peels and eats the potato with. He is an automaton, reduced to the level of a simple one-armed machine. He knows neither ambition nor emotion, except for passing flashes of anger erupting from the blanket of vegetative frustration that has come to form his core.

Again: “It’s ready.” One word in Hungarian.

They sit at the table.

Today we will watch the girl’s eating of the potato. She peels it using both hands with a studied delicatesse, perhaps wistfulness. While her father’s annihilative approach reduces the potato to burning mashed bits, the girl’s careful rationing allows for her preference of pronounced chunks. She blows the warmth out of each bit before masticating the few she requires, scraping the remains into a bin alongside the peels. The morose figure of the father, long ago finished, has already taken up his position at the window, where he dozes off to the gales’ tortured tune.

The wind. You could close your eyes for the entire duration and just listen to the film and come away with an understanding nearly equal to the experience of watching it. Weather, as is often the case in Tarr (i.e. the torrential rains of Damnation), is one of the main characters in the film. Its constant presence is mostly heard, only seen — felt — when the cabman and his daughter exit the cabin. It is the inner soundtrack to the characters’ lives, while the outer soundtrack — the music that occasionally creeps in to accentuate the overall poverty of the scene — is a single droning theme of sadness and desolation, excerpts from an infinite loop.

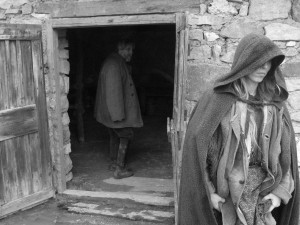

The placid calm of the second day is suddenly interrupted by the arrival of a third character into their lives. The importance of contrasts – dualisms, polarities, however you want to call it – will now be explicitly spelled out by his unprompted speech. Knocking on the door before entering, he comes like a prophet of truth into the lives of the cabman and his daughter. He is there to ask for a bottle of palinka. Like them, he is poor; unlike them, he still has a voice.

“Everything’s in ruin,” the man says, “everything’s been degraded…But I could say that they’ve ruined and degraded everything. Because this is not some sort of cataclysm coming about with the help of so-called innocent human aid. On the contrary, it’s about man’s own judgment, his own judgment over his own self, which of course God has a hand in, or dare I say: takes part in. And whatever he takes part in is the most ghastly creation that you can imagine. Because, you see, the world has been debased. So it doesn’t matter what I say because everything has been debased that they’ve acquired. And since they’ve acquired everything in a sneaky, underhand fight, they’ve debased everything. Because whatever they touch – and they touch everything – they’ve debased. This is the way it was until the final victory. Until the triumphant end. Acquire, debase. Debase, acquire. Or I can put it differently if you like: to touch, debase and thereby acquire, or touch, acquire and thereby debase. It’s been going on like this for centuries. On and on and on. This and only this, sometimes on the sly, sometimes rudely, sometimes gently, sometimes brutally, but it has been going on and on. Yet only in one way, like a rat attacks from ambush. Because for this perfect victory it was also essential that the other side – that is, everything that’s excellent, great in some way and noble – should not engage in any kind of fight. There shouldn’t be any kind of struggle – just the sudden disappearance of one side, meaning the disappearance of the excellent, the great, the noble. So that by now these winning winners who attack from ambush rule the earth, and there isn’t a single tiny nook where one can hide something from them, because everything they can lay their hands on is theirs. Even things we think they can’t reach – but they do reach – are also theirs, because the sky is already theirs and all our dreams. Theirs is the moment, nature, infinite silence. Even immortality is theirs, you understand? Everything, everything is lost forever! And those many noble, great and excellent just stood there, if I can put it that way. They stopped at this point, and had to understand, and had to accept that there is neither god nor gods. And the excellent, the great and the noble had to understand and accept this right from the beginning. But of course they were quite incapable of understanding it. They believed it and accepted it but they didn’t understand it. They just stood there, bewildered, but not resigned, until something – that spark from the brain – finally enlightened them. And all at once they realized that there is neither god nor gods. All at once they saw that there is neither good nor bad. Then they saw and understood that if this was so, then they themselves do not exist either! You see, I reckon this may have been the moment when we can say that they were extinguished, they burnt out. Extinguished and burnt out like the fire left to smolder in the meadow. One was the constant loser, the other was the constant winner. Defeat, victory, defeat, victory. And one day – here in the neighborhood – I had to realize, and I did realize, that I was mistaken, I was truly miserable when I thought that there has never been and could never be any kind of change here on earth. Because, believe me, I know now that this change has indeed taken place.”

“Come off it!” cries the old cabman in return. “That’s rubbish!”

The messenger silently shrugs his shoulders, takes the bottle, puts down some money, and exits.

The girl goes to the window, watches him walk away. He pauses, midway to the horizon point, takes a swig of the bottle. Under such conditions, it is best to be drunk. Besides poverty, drunkenness is perhaps the other of Tarr’s major motifs. This goes back to his great ode to beeriness, The Outsider, but recurs constantly in his films; there’s a rumor that Tarr insists that the actors actually be drunk when he films such scenes. Nobody wants to be drunk. People like to get drunk. With alcohol, it is always the process that matters. Alcohol is one thing that propels motion, movement, it is one means of propelling vehicularity through non-physical means. Under certain conditions, communism (Satantango), it was one of the only means of escape…

The girl continues staring. Until blackness is achieved, signaling the accomplishment of night.

Third day, girl gets up, well, two buckets of water, dresses father, father two shots of booze, girl takes one.

If The Turin Horse were, as the lazy critics proclaim, an apocalyptic film, then it would be set in the present or the near future; not the late-19th century, the height of modernity. But here we have our critics’ misunderstanding of the Horse’s dialectic with modernity. And to understand that, of course, then we have to go back to Nietzsche, to that moment that occurs off-screen before the film begins, that banal crazy moment that the father doesn’t even feel compelled to tell his daughter about: the crazy man who saw in the beast something that he himself is unable to see.

Father goes out to the barn. Daughter follows. Shovels manure. The horse shits but it will not eat. “She’s not eating,” the daughter says. “She will,” replies the father, walking away. “Eat,” the girl begs the horse. “You have to eat!” The horse stands facing the wall.

They eat their potatoes. In this scene, a wide angle is employed that allows us to watch both father and daughter eat at once, comparing the father’s scavenger ways to the daughter’s reservedness. Neither of them savors. Suddenly the father looks up; daughter’s gaze follows. A wagon approaching on the hilltop horizon. Gypsies. “What the fuck do they want here?” says the father, angrily.

The gypsies’ horses are alive and healthy, galloping toward them. The gypsies are free. They are unburdened by commitment. The gypsies approach the well and steal some water. The father and daughter chase them away.

One of the gypsies gives the girl a holy book. She sits in the house and reads aloud from it, about the necessity of a ceremony of penitence wherever a deed of injustice has occurred. Outside, the wind continues its punishment.

Day four. The well has dried up. There’s no more water, no more water. But there’s still palinka.

Daughter goes in to see the horse. “Why don’t you eat?” she asks. The horse won’t drink, either. She begs it. But no.

Back in the house, father decides they will leave. They pack up their belongings. They try to go.

Now, we watch them. They fight the wind by walking the empty field to the horizon point, disappearing behind the tree.

One minute later, they re-appear, returning.

We watch them re-trace their path. All in all, the scene – the going and the returning – takes about six minutes, this false exit and return. We do not know what discouraged them from venturing onwards. Perhaps the hopelessness of the situation, admitted defeat against the wind’s ceaseless violence.

Conditionality. It is the same now as it was then – despite our superficial notions of progress – resonating with Nietzsche’s cognizance of the cyclical nature of time. The eternal return. Go away and come back again: it is the same over there as it is right here. You do not have to venture very far to find this out.

From outside the house, we watch as the girl retires in front of the window, staring.

The world, in its duplicative essence, makes us stare at it out the window of our own thoughts.

Fifth day. Daughter dresses father. Palinka. Father goes to barn. The horse. They stare at it, then shut the barn doors back up. Th windy horizon as seen from the window. The father stares, stupefied into unconsciousness. Girl sews by the table. They eat their potatoes. Each single potato, as always. Father finishes first, as always, returns to his seat by the window. Nothing to do but remain passive.

That night, the oil lamps stop working.

No more water, no more fire – a reverse creation story.

Just darkness: the wind: a dying horse.

“Even the embers went out,” resounds the daughter’s voice.

“Tomorrow we’ll try again,” her father responds.

Horse and cinema are one and the same. They are both vehicles. Vehicles require fuel, sustenance, in order to continue living, breathing. The horse is a vehicle, this horse in particular is a cab, used to transport people from point A to point B. The body is also a vehicle, the vital essence of the body-mind machine; even when we stand absolutely still, our vehicularity is still operable: mind, an extension of body, is capable of moving the self aphysically through different domains, memories, images, realms of experience. In our “post-human” state — if a release from humanity is indeed what we as a species are truly currently yearning for — we are actually seeking a release from vehicularity. We no longer wish to be transported, all our longings have come to an end, stasis is the new world order. Instead, we have invested all our desires into a false god – technology – a false, outwardly-positioned vehicularity that provides little more than a dim superficial impression of motion, movement through the cosmos. An extreme limiting of possibilities: we no longer yearn for actual motion, but have been deceived by modes of illusory motion. Otherworldliness is no longer desirable, but total immersion in a world that does not, in fact, want us; a world we have divested of life force by allowing the opposing forces of mediocrity to assert and impose a system of false values. It is this process of investiture, of divestiture, that has been described by the visitor in his monologue, a process that the man and his daughter are unable, unwilling to acknowledge.

And Nietzsche? It could be said that it was his prescience that killed him, that drove him insane in the end. The horse he saw was not just a beautiful animal, but a symbol of all vitality. The moment that he touched the horse, Nietzsche lost his own vehicularity, becoming one with the horse, whose own process of loss — of surrender to eternal stasis — was well under way. Ensconced in modernity’s carcinogenic pathos – a West lost to mysticism and the numinous potentialities of the unknown, insistent on the toxic notion of progress – the “excellent,” the “great,” and the “noble” face a fossilized future, dim anti-projections of an under-nourished self that, rather than “post-human,” has become something less than human in an atmosphere that is defined by lack, where the winds are permanent and so nothing of any substance can remain for very long.

Here is what the triumph of mediocrity looks like:

The sixth day. Last four minutes before the film flickers out. Darkness. The pair seated at table. Their potatoes. Only now the daughter won’t eat. “Eat,” he tells her. He eats his potato raw; no water or fire to cook it. She silently refuses to eat hers. She has become like the horse. The father can’t finish his, either. Both stare downwards at their empty plates.

This essay originally appeared in ARC, the journal of the Royal College of Art.

2 comments

I believe this review of the greatest film I’ve had the privilege of watching,to quite possibly be the greatest review.

When hope has eroded all that is left is one of the scariest things imaginable.

by Samir Shukir on September 5, 2021 at 12:55 am. #

I think this is a brilliant write up of The Turin horse the only part I have a different view of is that Tarr was quoted as saying that he was to make one last film about the end of the world,then he was done with making films…but agreed,certainly to endure a life devoid of Art is to exist ,not live..

Melancholia may be a typical serving of Von Trier but I was surprisingly mesmerized by the visuals and the way the human elements held sway cinematically in this film,made the Sci-fi all the more powerful..I felt shades of Tarkovsky here. .2great films though the Hungarian directors offering is far and away the best I’ve seen…need to see Faust next!

by Aldo Cinoa on April 14, 2022 at 4:37 pm. #