Rauschenberg: 1925-2008

by Travis Jeppesen on May 20, 2008

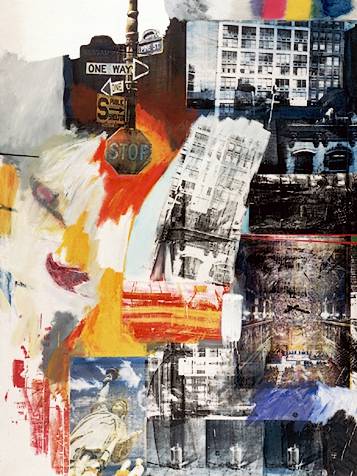

It’s hard not to fall into the trap of thinking about Robert Rauschenberg from a historical perspective. Like two of his lovers, Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly, he is frequently seen as a transitional figure, and perhaps more than the others, he was the artist whose work formed a bridge from the Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s to the Pop Art of the 1960s. By circumstance, he was also the first artist to introduce the enfant terrible notion into the American art world, becoming infamous – if not openly despised by the critical establishment – with his first exhibited works, which no one could make sense of at the time. For many, that struggle continues.

One typically becomes the establishment by resisting it for the vast duration of one’s life. Rauschenberg got “in” early, then went back “out” as soon as he could, living for much of the latter half of his life on an island off the coast of Florida in relative isolation from the rest of the so-called art world. He never really evolved much as an artist – his work either stayed the same or grew less interesting as he got older. He kept making it, though. I haven’t seen enough of the later work to pronounce judgment on it, but perhaps some enterprising institution will throw together a definitive exhibition of the later work, from 1970 up to 2008, to allow the public to decide.

My own relationship to Rauschenberg’s work is so personal that it makes it difficult for me to trust my own judgment. I wasn’t able to start looking at art seriously until 1997, when I moved to New York for college. Wandering through that city’s great permanent collections, Rauschenberg’s combine paintings had a strong impact on my developing sensibility (which some might call an anti-sensibility.) There was something jarring and anti-aesthetical about his work from the 1960s that I most likely related to through punk rock, my sourceless anger. Rauschenberg assumed the role in art that Kathy Acker assumed in literature. I tried – unsuccessfully, of course – to imitate both, because imitation is what you do early on in life when you have yet to find your own way.

As I grew up, traveled, and looked at more art, I began to have severe doubts about my initial estimation of much of Rauschenberg’s work. The problem for many, of course, is the fact that Rauschenberg’s work rarely looks good. I could never wholeheartedly subscribe to a blanket denunciation of his work (such as Jed Perl’s), because some of it does cohere on a visual level. There are a lot of failed experiments out there, but there’s a quality of motion and rhythm in a lot of his larger paintings that I find completely compelling, even when they make me dizzy and nauseous. A lot of his paintings seem like anti-design. In actuality, I think they represent total design – by going back to foundational design principles.

Still, what remains the most disruptive feature of Rauschenberg’s art is its brutal lack of definitionality. He famously quipped that he wanted to erase the artificial barrier separating art from life, and thus became an ambassador of openness – the American equivalent to Joseph Beuys, but with a markedly different way of going about it. Just as he once erased a de Kooning, he might as well have erased himself, because he wanted his art to be viewed by the world as a creation of the world. The world in its comeuppance, its severe vision of things. He started out as a naïve outsider from a provincial nowheresville, and graduated back into the obscurity from whence he came. With Rauschenberg, it is perhaps still too early to assess the true value of his work.

This piece originally appeared in Think Again, Prague’s free city magazine in English.

Leave your comment