Guma Guar

by Travis Jeppesen on April 3, 2008

Guma Guar

Guma Guar is a Prague-based art collective. Through their live actions, interferences, exhibitions, breakcore activism, and resplendent energy, they continue to expand and revise the possibilities of art in the 21st century.

This conversation recently took place via e-mail, as Guma Guar was making preparations for their upcoming exhibition at Prague’s Old Town Hall (April 23rd – June 1st, 2008.)

What does the group Guma Guar stand for? What is it that you do?

The origin of our 3-member art and music group Guma Guar began in 2003 and was initiated by the inner need to publicly express our opinion on certain controversial and problematic public issues, rather than navigating ourselves through the art world based solely on an egoistic presentation of our own inner worlds and building careers, as it is done by most artists these days. There are many artistic groups on the Czech art scene whose art is often described as political or tendentious – according to our view, they are not critical enough and their criticism is too often focused on “official goals” convenient for the current power elite. The initial central theme of Guma Guar’s work is the disputation of the function of the capitalistic world system, criticism of western militarism, questioning gender, issues of minorities, a critical analysis of the cultural industry, and a commentary the function of mass media in today’s society.

Who are the people behind Guma Guar? Or, if your members choose not to identify themselves, can you explain the reasons behind your anonymity?

The group consists of three white heterosexual individuals of male gender living in Prague. Even though the names of these individual members are not explicitly secret, we do not like to mention them in connection with Guma Guar projects. After all, the group was created partly as the expression of a certain skepticism towards the model of the individual artist. At the same time, it seems that our collective identity offers kind of a better legitimacy as commentators of political happenings than we could accomplish individually. Our group activities do not exclude solo activities of individual members.

How does the collective function? Are ideas thought up and executed by individuals in the group, or is everything conceived and executed by the entire collective?

Essentially, we function through both of these principles. Once in a while we have a meeting, which we call brainstorming, as a funny reference to work in advertising agencies. During these meetings, we discuss topics that we consider important. Eventually, we develop concepts that are already partly concrete. It also happens sometimes that one of our members comes with a finished or almost-finished work and there is no need to finalize it if other members agree.

Many – if not most – of your works seem to be rooted in an aesthetics of disruption. Is Guma Guar affiliated with any particular ideology? People often speak of you as anarchists. If this is so, do you adhere to any particular branch of anarchism?

Although we don’t conform fully to any concrete “meta-narration,” we would most likely localize ourselves somewhere on the intersection of moderate anarchism and neo-Marxist tendencies.

In every case, cornerstones remain mainly the (revised) teachings of the so-called Frankfurt schools (Marcuse, Adorno, Benjamin, Fromm), the soft-anarchist theory of The Temporary Autonomous Zone by Hakim Bey, texts by Noam Chomsky, essays by the sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, and the Czech philosophers Václav B?lohradský and Antonín Kosík.

Lately, we have found interesting some opinions of the duo Antonio Negri & Michael Hardt, or the new book Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein. We could follow name dozens of other texts that are reflected in the work of Guma Guar’s work.

To put it simply, our fundamental “program” is “a critical view of society.” In our opinion, without it, the current society will fall into a morass of consumer totality.

Do politics really have a place in art? Aren’t you “preaching to the converted,” in a sense, as most of the people who see your work already hold similar political views as yourselves?

We are not really sure that the majority of our hypothetical audience shares the opinions we present. We think that the spectrum of our viewers is fairly unmonolithic in terms of the places we use, such as galleries, the street, clubs, free parties… Even the opinions of gallery visitors do not fully correspond with ours. Often controversial exhibitions are discussed in the media, thanks to which the discussed topics reach a wider public.

We believe that there is a space in art (as it is a mirror of society) for everything that creates this society – and politics is important mainly in a democratic society. All art has a political dimension.

This interview is reprinted from Think Again magazine.

The “Lost” Art of Art Criticism

by Travis Jeppesen on March 31, 2008

In a recent editorial addressing the endless debates over criticism’s role in the current art world, Damon Willick argues that such debates often reduce the so-called crisis to a binary opposition – Greenbergian formalism vs. postmodernism. Proponents of the former accuse the postmodernists of academic obscurity, political correctness, and an inability or unwillingness to pronounce judgment on the quality of a work, while the postmodernists accuse the formalists of being elitist and conservative in their defense of the canon. Reverting to a past model – i.e. Greenbergian formalist – is inappropriate for historic reasons, as much of the art being produced today is coming out of a worldview informed by postmodernism, post-structuralism, and all the other posts we lug around with us, whether out of laziness or a sense of defeat. Willick denies that there is anything remotely resembling a crisis in either art or art criticism, arguing that criticism must adapt itself to the conditions of the present rather than prolonging a never-ending debate that is binaristic, and hence reductive. (In arguing thus, Willick is of course aligning himself with the postmodernists, whether he realizes it or not – ultimately, one cannot escape one’s education or position in the historical present, and this is something that Willick argues as well.)

I agree that it would be pointless to revert to a Greenbergian mode of formalist discourse when writing about art. It would be almost like if a novelist, bemoaning the state of the novel in the 21st century, reverted to penning novels in the style of Charles Dickens. But I also feel that Willick misses some important points – as did Clement Greenberg, and all the other “authorities” typically cited in these endless debates.

What is at stake here is language and the ways in which it is deployed. The debates over the purpose of art criticism seem to ignore the simple, basic fact that the art of art criticism is in fact a literary art.

Greenberg decried the poetic obtuseness of criticism in his time in favor of a direct form of plainspeak that was meant to convey the critic’s judgment of the artwork’s aesthetic worth.

The postmodern, or late 20th century/early 21st century model of art criticism, according to people like Willick, is rooted in the verbosity and heady conceptual paradigms of (mostly French) critical theory – a language that the layman could never comfortably enjoy.

By insisting on aligning yourself with one of these two camps, Willick infers, you are limiting yourself as a critic.

What Willick neglects to observe is that, if there is a threat to art criticism, it is neither the formalist impulse, nor the jargon-laden antics of the posts, but the social conditions of the art world. Most of what passes for art criticism these days is not criticism at all, but propaganda. The dialect that has been adapted by most working in the art world is PR-speak. When concepts borrowed from critical theory creep into this language, it is almost always in a debased, watered-down form that shows little understanding of these concepts’ potential applicability to the works under scrutiny. The malaise that art criticism in fact suffers from does have a name, and it has nothing to do with the binary described by Willick: in a word, it is a lack of integrity. Once you are in a position where the market dictates all the terms and conditions, then language follows suit, and you are no longer living under conditions of great possibility, but under intellectual slavery.

Another point that Willick fails to pick up on – and this might have something to do with the fact that he is writing as an academic – is the fact that not only is Greenbergian formalism outmoded, but so is the po-mo discourse that he assigns to such figures as Arthur Danto and Katy Siegel. No one but the most naïve undergraduate is going to be impressed by your “deconstructive reading” of a work of art in 2008. Readers are much more interested in the prices that works fetch at auction than they are in that sort of (pseudo-) mystification. The monetary value naturally also takes precedence over the aesthetic value that any one critic may attempt to assign.

I’m not about to argue that criticism’s central task should be to take on all the corruption rampant in today’s art world. But anyone who practices art criticism today should be mindful that it is not their duty to uphold individual careers, but to find new ways of engaging with works of art through the medium of language. If there is anything to complain about, it is the fact that in most criticism these days, one finds a stunning lack of multidimensionality in writers’ ability to think about language. Every sentence construction conforms to a certain crude type, readers become bored with the monotony and give up on criticism altogether, and the writers gripe about being ignored.

Art criticism must continue to grow and develop alongside the art that it takes for its subject, while remaining mindful of the seemingly paradoxical premise that history is not a linear progression, but comprised of cyclical occurrences. Rather than dismissing Greenberg or anyone else out of hand, such writers should be acknowledged as useful referents – but not as a foundation. Each critic must build their own foundation in seeking out new languages and new forms with which to engage – and pass judgment on – the objects and images they surround themselves by. Only then will we see a solution to what I suspect the real problem that Willick and so many others are grappling with – the lack of a veritable renaissance in contemporary art criticism.

IN MEMORIAM: Jan Jakub Kotík (1972-2007)

by Travis Jeppesen on March 29, 2008

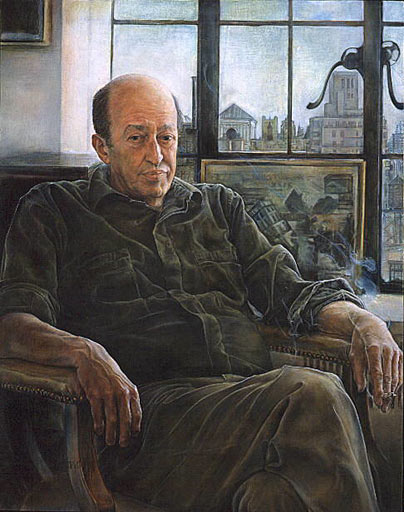

In December, the Czech Republic lost one of its most promising young artists to cancer. I first came into contact with Jan Jakub Kotík when I was commissioned to write an essay on his work by Umelec. I did not know Jan well, but I quickly became a fan of his work, and was fortunate enough to spend a few hours in his presence. While I have never been a huge fan of conceptual art, and have long felt that it is needlessly overdone in this part of the world, Kotík’s work was imbued with a freshness and fierceness that is frequently unsettling. Kotík wasn’t merely a brilliant conceptualist; he was also a highly skilled craftsman – a combination that has become increasingly rare in this age and milieu.

Jan’s work was not the only thing that made him an enigma in the Czech art scene. An American by birth, a New Yorker by training and default, Kotík was ultimately a Czech – and from one of the country’s most distinguished families at that (his great-great grandfather was Tomas Garrigue Masaryk.) While the biographical details surrounding Kotík and his family are intriguing, it is for the extraordinary body of work left behind that Jan will ultimately be remembered.

Kotík first caught the attention of the artgoing public in 2000 with his solo exhibition, Economies of Scale, in which he exhibited tiny household appliances intricately constructed out of model airplane and tank parts. What seemed at first like a joke was actually a startling commentary on the corporations that produce mundane household objects – the same manufacturers responsible for the development and production, in collaboration with the U.S. government, of radar technology, guided missiles, spy ware, satellites, and various other militaristic technologies employed in the wars of the last century.

Kotík’s best-known work, however, is probably Hail to the Chief. The piece is comprised of a floor-to-ceiling stack of “Marshall” amplifiers that the artist actually built himself, with the American presidential emblem emblazoned on the center in gold. The speakers blare a modified sample of the guitar intro to Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man,” which is digitally manipulated to evoke the sound of air raid sirens and planes flying overhead. Heavy metal and fascism converge in a singular synaesthetic invocation of the global political deity himself. The piece not only transmits an ironic political message through its loud appropriation of national imagery, but provokes a range of contradictory emotions that the viewer is forced to confront.

From talking to Jan, I got the impression that he truly loved Prague. Like a lot of gifted young people living in this city, however, I think he also felt frustrated at times by the fact that artists here are only reluctantly given the attention they deserve – and seldom in doses that one needs to develop. Jan enjoyed being a part of the local art scene and loved to indulge in gossip about its protagonists, just like the rest of us. At the same time, having spent his formative years in New York, where he studied at the prestigious Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, I think he also felt stifled by the pettiness and provincialism that often shades foreigners’ impressions of the Czech art scene.

Outside of the time I spent admiring his work, I’ll always cherish the precious few memories I have of the time I spent with Jan. We bonded over our mutual love of heavy metal, and shortly after I finished writing my piece on his work, we celebrated by attending a Cannibal Corpse concert. We always promised to hang out more often, but as sometimes happens, our lives wound up taking different paths. I stopped seeing him at art openings for a while and imagined that he had retreated into artistic seclusion. That was when I began hearing that he had become sick.

The last time I saw Jan, however, he seemed happy and healthy, and casually referred to his illness in the past tense. We bumped into each other on the number 12 tram at Strossmayerovo Námestí. It was a beautiful day in the sweltering summer of 2006, and as the tram eased along the side of the Vltava, the sun’s rays shimmering on the surface of the water, we talked eagerly about art and life. Things seemed to be going well for Jan. He was being represented by the newly established hunt castner artworks, which was already being invited to display its artists’ work at respected international art fairs. His wife had just given birth to their first child; a second would be born before he passed away on December 13th. We talked excitedly about my upcoming move to Berlin and eagerly agreed to meet up for a beer before I left town. But life does its thing, and for whatever reason, we were unable to fulfill our promise to each other. I stepped off at Švandovo Divadlo, and waved goodbye for the last time.

Death is unfair. It has robbed Jan Jakub Kotík’s wife of a loving husband, his two children of a father they will likely have no memories of, his parents of a son, and his brother of a sibling. But for most of us, the real tragedy of Kotík’s death at such a young age is the fact that his work never got the recognition it deserved in the course of his lifetime. Like Eva Hesse, Steven Parrino, Jason Rhoades, and so many other artists who were taken away from us while in their prime, it is now up to history to call the shot that is rightfully his.

This piece originally appeared in the magazine Think Again.

Four Films by Mark Ther

by Travis Jeppesen on March 27, 2008

1. I Will Get You Out and Chop You Up in Midair (2007)

Plants. Flowers. I don’t know the names of any of them. A chair in a garden, an assortment of tools. The chirping birds are so bored, can’t you hear them. Why do we generate nature in our own backyards. A dead man in the garden. Blood all over. Another bloody man, alive, sits close by, staring through the shrubbery at the deadness. The dead man wormcrawls across the grass. In French, the living recites the following text:

It’s pathetic that you believe in instincts. Everything we’ve been taught, think…

It makes me sick, the way you treat me.

You don’t want to open your heart to me, why? Because you consider me as a man, is that why?

I am very sad that I can’t touch you and you don’t want it, that’s it…

So you want to be like all the others, the motherfucking heterosexuals with an inferiority complex and without fantasy?

There is so much inside of you, such a wide range…

Degenerated male?…

To shove a dick inside of a stinky twat, a hole that leaks blood… Does that feel nice?

Why do you not want to try something different, something that isn’t appreciated by society?

You mean a lot to me, you know that…

You dick will fall off after sticking it into a twat.

I miss you…

The tenderness which is inside of you can’t be covered by maleness.

Name…

And what now?

The dead man touches a flower.

2. Hanes (2007)

Two dead faggots in their Prague apartment. They wanted to move to Berlin, but they never made it there. Their names were Mario Dzurila and Travis Jeppesen. They killed each other in their Hanes.

3. Be Quiet, There is a Cow Farting in the Stable (2007)

A Nazi soldier goes for a stroll with a young boy around the castle grounds. The two are in love with each other. Or maybe it is just lust on the Nazi’s part. They frolic in the field. The story of the Nazi’s arrival is told in flashbacks. The war is going on, Czechoslovakia is occupied, the Nazi has come to occupy the castle. Looking out the window, the Nazi and the Proprietor watch as the boy drowns in the lake. The Nazi asks if he can see the Proprietor’s bedroom. The Proprietor tells him he has many bedrooms in this castle.

4. Was für Material! (2007)

Gay love lives of the Hitler Youth. Tonguing the flame. Running through the fields, Nazi flag in hand. Pissing on crosses and licking it off. They are happy to know each other.

Mark Ther’s Television Commercials

by Travis Jeppesen on March 26, 2008

Mark Ther is a Prague-based video artist.

These are some of this television commercials.

His work is the subject of an essay in my forthcoming book, Disorientations.

Tomorrow, I’ll be writing about four of his recent films.

New Kid on the Bloc

by Travis Jeppesen on March 25, 2008

Jon Campbell

Galerie Deschler, Berlin

Through March 29, 2008

At Galerie Deschler, hidden away down in the basement, a young American painter by the name of Jon Campbell is having his first solo exhibition in Europe. It’s rare to find an artist so young who already possesses such a clearly defined, well thought-out vision.

Campbell is primarily interested in disjunction. The arrangement of the paintings in the show represents a downward slide, from formal perfection to deformity and mutilation, or just plain wrongness. The human figure serves as the foundation of Campbell’s pictorial interest, but even in the straightforward portraits we find in the first half of the exhibition, the final execution seems to serve as a departure point for probing issues of a more existential nature.

While his drawing is always impeccable, what ultimately jolts you when standing in front of Campbell’s paintings is the subtlety of his palette. The two ultimately serve each other, however; Yoshitomo Nara may be similarly skillful when it comes to handling his pastels, but Campbell’s technique – not to mention his probing subject matter – makes Nara appear desultory.

The one artist Campbell occasionally calls to mind is Francis Bacon, particularly in a painting like Parallels (2007). The backside of a naked, obese man is seated on a brown rectangle, which has been rendered in a thick line. The man is perhaps underwater, perhaps masturbating; it’s hard to tell. An ashy blue background fills the bottom ¾ of the canvas, with a darker hue slicing through the top. Where this second background interrupts, it also cuts off the figure before we even make it to his shoulders. What is left is less a torso and legs than a wallop of fleshly sludge.

It is in his backgrounds that the artist is able to lose himself in a dreamy mirage of color that is never laid on too thick, despite an obvious reliance on overpainting in such works as Snafu (2007). Restraint is key here, but it never happens at the expense of texture.

And then, something happens. A vacant stare gives way to a blindfold. Faces are blockaded by the superimposition of other images. The painter becomes less interested in figuration, and more caught up in disfigurement – birthmarks, scars, severed body parts deserted scapes. This arrangement of canvases culminates in an untitled painting from 2006. It is a painting of a figure ravaged, an image of total human deformity set against an apocalyptic purple background. While such a bleak, powerful image of the human condition in an increasingly uncertain world had been hinted at before, in the playful surrealism of Target and the cynical superimposition paintings (Asylum and Narcissism), it is upon arriving in front of this painful inquiry into suffering that we ultimately realize what is being solicited. And only an artist as uncompromising as Campbell can make us see it.

On the Expulsion of the Friendless Warrior

by Travis Jeppesen on March 22, 2008

Why do we read art magazines? Sorry, but it’s a question that needs to be asked every now and then, as the answer seems to change over time according to one’s position, status, and relationship to the rest of the so-called art world, if such a world actually exists. Do we read in search of some projection of our selves, whether direct or indirect, on glossy pages? To keep abreast of the latest trends so we don’t feel left behind? And, when we finally get past the voluminous deluge of advertisements, do we flip through or actually read the text? Does anyone care anymore about what the critic has to say? Is there still such a thing as an independent critic, unaffiliated with any art institution?

These are the questions I inevitably wound up asking myself after reading the latest issue of BE Magazine, a slim journal published under the auspices of Berlin’s Kunstlerhaus Bethanien. Issue number eleven is dedicated to the theme of “Critique” and kicks off with Hanno Rauterberg’s compelling essay addressing the current crisis of criticism in art. Departing from the provocative statement that if art criticism were to fall completely silent, nothing would change, Rauterberg goes on to argue that criticism’s central tenet, to make a judgment, has become a thing of the past. While acknowledging that this “death of criticism” proclamation is nothing new, Rauterberg maintains that the crisis of criticism has led to self-abolition in favor of a “falsely understood desire” to be objective. Criticism, as a serious intellectual discipline, cannot afford to be objective, reasons Rauterberg; as soon as you lose the “I,” it is no longer criticism. As Leibniz taught, all perception is determined by the point of the perceiver. Criticism has been replaced by a new sort of art writing that is little more than propaganda for exhibitions and individual careers.

Rauterberg’s essay brings up several good points. Why are there so many artists and so few critics these days? It used to be that a review could make or break an artist’s career. Not so anymore. Critics are simply not adorned with that sort of power. When evaluating the history of the 20th century, the critic emerges as an agent of Modernism. It is important to remember that it was actually a poet, Charles Baudelaire, who thrust art criticism into the realm of Modernity. Baudelaire, an artist himself, thus made criticism an art, by constantly questioning and re-evaluating his own principles. In America, there’s the famous example of Clement Greenberg, champion of Abstract Expressionism and formalist criticism, and his disciples, as well as the Australian expatriate Robert Hughes. Baudelaire, Greenberg, Hughes: three household names in the history of art criticism. Is there any other living figure, besides stodgy old Hughes, whose name possesses such authority?

This loss can be attributed not only to increasingly conservative attitudes in the field of publishing, but to the introduction of trans-disciplinary practices in the arts sector. Under the potentially illusory guise of freedom, there has been a complete breakdown in the definition of the term “art world professional,” to include a wider matrix of professional activity. Today’s critic is also a curator, a museum director, an editor, perhaps even a visual artist herself. How can this critic write a negative review of an exhibition at a gallery where she hopes to one day curate an exhibition?

What Rauterberg is essentially proposing is the re-introduction of a more rigidly defined professional sector, as per the model evolved throughout the course of Modernity. But another option would be to deny this “death of criticism,” and simply recommence our contribution to the continual evolution of this “lost” discipline. We can start by listening to some of the voices outside the narrow realm of official art discourse, and to integrate some of those renegade outsider voices into the artspeak that has been emerging since the dawn of conceptualism and has of late fallen into a completely false “specialized” (pseudo) language rife with the sort of verbose inanities that so effectively exclude those un-savvy enough to challenge the art world’s web of hierarchical systems.

Furthermore, instead of relying on these tired categorical contingencies, we should be working to develop new art languages that refute criticism’s traditional limitations (i.e. didacticism). Language is not a system of goals, not an end in itself, but a savage beast yearning to be set free – we must let go and allow this beast to roam about and possibly do some harm, possibly even devour the very principles that we hold most sacred, to the extent of erasing the very thing we wish to communicate. In short, the future will require the emergence of a new criticism that manages to maintain its edge while returning to its poetic origins. Perhaps this wild new fornication of raw language and raw philosophy will occur in a medium other than the written word; perhaps it will be activated digitally; perhaps it will resemble the wild illegible graffiti found in Cy Twombly’s paintings… The primary goal should be not to judge, nor to nurture (although it can do both), but to ultimately confound us, thus spurning a more active engagement with the art object through its mysterious anti-nature, thereby bringing us closer to the Truth, which is always synonymous with Confusion.

Originally published in Umelec, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005.