Gilbert & George @ Artforum.com

by Travis Jeppesen on July 5, 2009

My review of Gilbert & George’s current Berlin exhibition is now online.

WHITE TRASH DUMMIES

by Travis Jeppesen on July 3, 2009

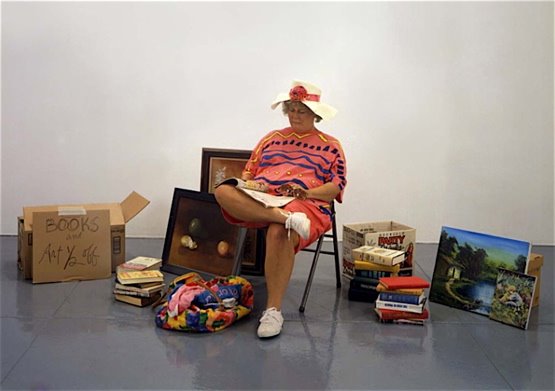

On a recent trip to Paris, I was lucky enough to catch an exhibition of Duane Hanson, whose work I’ve long admired in reproduction but seldom seen in actuality. The sculptures most people and I know best stem from the latter half of his career, when he took to creating lifelike reproductions of mostly white trash. People that most people consider to be white trash. I don’t use that term in a derogatory sense; these are the people you will likely be surrounded by your whole life in America, unless you come from a place like New York or Los Angeles or are incredibly wealthy and choose to live isolated among other incredibly wealthy people. I don’t know that I buy the argument that Hanson’s work comes out of social realism. That would imply that whatever social commentary you can wrench out of his work is more important than other factors, such as the mood evoked by the sculptures. That a profound melancholy haunts all of these sculptures dispels that notion. I would go so far as to say that Hanson is more of a melancholist than a social realist. At the same time, it is difficult to tell whether he has any real compassion for his subjects or not. He chose to live in south Florida for the vast majority of his life. I’m also from south Florida, and while I didn’t grow up there, I spent enough time there as a child and adolescent to recognize that it’s one of the trashiest regions of the United States. I think there are many ways you can interpret Hanson’s attitude towards his subjects – and the most popular of them are condescending. You can say he has great empathy for the subjects he depicts, which implies that he feels sorry for them, or you can say he depicts them in a very brutal manner, meaning he is making fun of them. This points to a problem of interpretation within the context of the art world, though – not within Hanson’s work.

Duane Hanson – “Illusions Perdues”

Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin

Paris

Through July 11th, 2009

8th Baltic Contemporary Art Biennial – Szczecin, Poland

by Travis Jeppesen on June 6, 2009

Armando Lulaj, Time Out of Joint

Szczecin is among the most depressing cities I’ve visited in Poland. I won’t say it’s my least favorite – that distinction would have to go to Zakopane, that overcrowded resort haven in the Tatra Mountains near the Slovak border, teeming with Russian ski tourists, bad food, and tacky souvenir shops. Szczecin is its own unique case – battered by time, it wears its scars with an indifference marked by uncertainty. It was used as a port for Berlin during the Second World War and was heavily bombed. Reconstruction continues to this day, and one can hardly call the process a success story. Scattered renewal jobs on buildings from an array of historical styles have been attempted, only to be interrupted by one communist eyesore after another, the biggest one of which is undoubtedly the main avenue running through the center of town – little more than a six-lane highway lined mostly with shops selling crap you wouldn’t want to look at, let alone buy. If Krakow is heaven and Zakopane is hell, Szczecin is truly purgatorial – you might not get killed there, but you’re not going to have the time of your life, either.

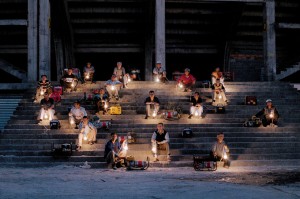

Just as the city seems to be struggling to evolve a coherent identity, so a sense of displacement haunts the latest Baltic Contemporary Art Biennial. A struggle to not forget while surviving. In this sense, Adrian Paci’s short film Turn On captures the mood perfectly. Shot in the artist’s native Albania, the film consists of a series of close-ups of the faces of a group of middle-aged men who seem tired and weathered by waiting. The film then moves to a distant shot, allowing us to see that the men are seated on the steps of a worn, abandoned building. Each holds a lightbulb attached to a power generator. It is a simple, but powerful metaphor of waiting to catch up to the speed of the rest of the world, yet feeling the threat of being left behind forever. It gives us an acute sense of time’s cruelty.

Joanna Rajkowska, Camping Jenin

Joanna Rajkowska, Camping Jenin

The chosen artists’ concerns are largely political – hence, the documentary mode is quite heavy. Joanna Rajkowska’s Camping Jenin documents a theater workshop for young men in a Jenin refugee camp on Jordan’s west bank. All of the men had their childhoods shattered somehow by violence, having witnessed their families and close friends get killed; most of them struggle from post-traumatic stress syndrome. The workshop thus becomes a therapeutic way for them to re-build their lives while addressing the source of their pain. The most fascinating documentary work, however, can be found in Kalle Hamm and Dzamil Kamanger’s excavationary approach to Afaryan, which poignantly explores an abandoned Kurd village in Iran through the memories of its former inhabitants.

The work is not all so heavy and literal. Johan Muyle’s motorized sculptures, which look like they were concocted with materials found at a flea market, are fun and random and deranged, while Armando Lulaj’s Kafka-esque Time Out of Joint shows us what happens when a large block of ice mysteriously appears in the middle of a rubbish dump outside of Tirana.

The Baltic Biennial is actually much smaller than its name implies – and this is its strong point. It designates a path that is quite manageable, and allows the casual visitor to devote much more time to individual works than at most biennials. In this, curators Magdalena Lewoc and Marlena Chybowska-Butler have done an adequate job of condensing the biennial to fit the scale and feel of Szczecin itself – a place way off the beaten path that has nevertheless been severely beaten.

Adrian Paci, Turn On

The Baltic Biennial of Contemporary Art runs through July 12, 2009.

PREVIEW: The 53rd Venice Biennale

by Travis Jeppesen on June 4, 2009

The major challenge faced by anyone asked to curate a biennial today – and this is especially true in the case of Venice, the biggest baby of them all – is that the task is simply an impossible one. No matter how all-encompassing one’s concept is, a slew of detractors will always be on hand to point out the gaps and inconsistencies. While there may be ways of getting around this in lesser biennials – focusing on the local, for instance, or splitting the main exhibition up into smaller curatorial projects – Venice, by its very girth, poses its own unique problems. The bottom line is that Venice is meant to be an index of all current trends in art – an impossible feat in itself; the trick is configuring a way to at least partly meet this task, while simultaneously designating some sort of conceptual approach to the problem that won’t falter beneath the mass of work to be displayed.

[Read the rest of my Venice Biennale preview piece at Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art.]

Terence Koh @ Peres Projects

by Travis Jeppesen on June 3, 2009

Those of us who have watched Terence Koh’s meteoric rise with grotesque fascination have always wondered how the inevitable obverse process would measure up to the hype spectacle. His current exhibition indicates that the fall will be swift and dismal.

Koh is showing a single sculpture, Boy By the Sea, a work that featured in a performance of the same title that took place at last year’s Yokohama Biennale. The sculpture, a miniaturized likeness of the artist sporting bunny ears, was carried totem-like by a mini-procession of loin-clothed young men and placed in front of the sea, at which point each of the young me stepped forward and tossed a single pearl into the ocean.

At Peres Projects, Koh has placed the sculpture on a wooden pedestal in the furthest room from the entrance. The sculpture is at the back of the room facing the wall, and is covered with a white transparent cloth. A second, empty pedestal stands next to it.

Like much of Koh’s sculptural output, the work is slight and inconsequential. One of Koh’s fumbling attempts at a signature is his usage of an array of materials, many of them perishable, which tend to give his sculptures their rough, crumbling appearance. (This has notoriously been a touchy subject for collectors who have paid extortionate sums for Koh’s work only to have it fall apart in the living room.) Here, fish scales, faux pearls, and pigments of white powder are among the substances tossed off. The wooden pedestal is artfully split in a few places, as though someone had jumped up and down on it a few times. There is no viable tactility to the piece; it is neither smooth nor rough – just a clumsy stab at a unified whole. Although some critics have struggled to articulate Koh’s haphazard usage of unusual media as a sign of the artist’s virtuosity, I can’t see it as anything more than a total lack of sensitivity towards his chosen materials.

Regardless as to whether your focus is on the whats or the hows, there isn’t much going on in Koh’s sculpture. Then again, the illusion that Koh has anything significant to express can only be understood as a symptom of the excesses of the Bush era. Koh’s highest achievement to date is his persona – this, rather than the work, has always been his fans’ focus. Figures like Koh satiate an audience obsessed by the glamour and decadence at the high end of the art spectrum, but care very little about the actual art. Painfully aware of his own limitations, Koh actively discourages us from taking a closer look, shining blinding light in our faces, as in his untitled installation at the Whitney, or covering the object of contemplation with a white cloth and turning it ashamedly towards the wall, as in this current Boy. It’s only a matter of time before the fantasy of Terence Koh’s artistry crumbles, in concert with much of his work. Before that happens, perhaps Koh will make good on one of his countless cynical assurances that he intends to retire from art altogether. From Boy By the Sea, one gets the feeling that he has already given up.

HAU Curator Stefanie Wenner interviews Travis Jeppesen about DADDY

by Travis Jeppesen on June 1, 2009

SW: DADDY is the title of the play that you wrote for our Festival “Your Nanny Hates You!” Fathers seem to be more and more absent, the construction of the postmodern family seems to move beyond the older notions of the threefold of father, mother and child. What do you think: Which place does the father have in the contemporary construction of the family?

TJ: When I hear the word “family,” it still calls to mind the archetypal three-part structure, as I believe it does for most people. In that respect, I don’t think the traditional notion of the family has changed all that much – as a pure semantic concept, that is. I think you’re right in assuming that it is more useful, then, to explore the changes of the individual roles stuck in that triangle. But I think Daddy is necessarily more suggestive than explicit in its positing of a New Father type.

SW: Religion is important for the story told in DADDY. Do you think it still plays an important role for contemporary ideas of family?

TJ: The way religion plays out in Daddy is quite specific. I’m interested in the ways that familial formation occurs outside of the classical Freudian triad (as discussed above.) This has a lot to do with being a societal outcast – being in a position where you feel that you’re forced to create your own family. This seems to be what happens in a lot of new religious movements, referred to in common parlance as cults, one of which is at the center of Daddy.

SW: The frame of the whole Festival discusses questions of intimacy and economy, the correlations of work, public and private life. How does DADDY fit in the frame of these questions?

TJ: For me, the question is: What is “private”? In our relations with others, how do we manage to properly cordon off certain interactions, while allowing others to be carried out in full view? The sexual revolutions of the ‘60s and ‘70s projected a world where fucking in the streets would become a norm. Only those of us dwelling in the Thought Ghetto seem to remember these promises. With the rapid expansion of technological possibility, previous definitions of privacy – and self-exploitation – are no longer valid. Anyone can be a porn star now; it’s not a taboo subject anymore. Has this expansion/intrusion into the private aided us in the project of self-knowledge? That’s one question that comes up in Daddy.

SW: When it comes to caretaking, neglect and incest seem to be close relations. How does DADDY tackle these issues?

TJ: Well, it is for this reason that I feel that Missus Pringles, the mother, may be the most interesting character in the play, because she certainly is forced to take on this schizo project of parenthood. Care ultimately begins with the self, then extends outwards; “good parenting” seems to deny this, in denying the primacy of the self and privileging the child as the only extension of the self that should matter; it’s built on a rhetoric of sacrifice; you know, “Save the Children,” “I Believe the Children Are the Future,” all of that sentimental bullshit.

The examples of “bad parenting” I most often witnessed while growing up in suburban America in the 1980s were the exact opposite situation, and came out of the damaged pseudo-ethos of the “Me Generation” of the decade prior. It rationalized parental neglect in the pursuit of “self-development,” reasoning that this will somehow make one’s children grow up to be strong, independent adults.

There are serious problems with both of these models, and Missus Pringles doesn’t really fit into either. Rather, we watch her struggle with the multiplicity of roles she has accepted – mother of Denny, wannabe actress, wannabe spiritual being, etc. – her struggle to cohere as an individual. She winds up using her son not merely as an extension of her own being-in-the-world, but as a sort of weapon against that world. Is there a sexual component to this? There’s no incest, per se, in the script – at least it’s not overt. She refers indirectly to the Josef Fritzl incident in one of her monologues, but I think that’s as far as it gets. Perhaps this question will re-emerge in the rehearsal process, I can’t say now for certain.

SW: What else interests you about the project?

TJ: I view the project as an opportunity to further interrogate the supposed discrepancies between the mundane and the numinous, two poles that have been at the center of my work for sometime now – the way in which they in fact enclose, rather than oppose, one another. I believe that Ron Athey has deeper insights into this question that will prove to be very illuminating. I’m interested in the shifting values of the “white world,” which is why we’re deliberately stating that the setting of the play is Europe and/or America. And I’m interested, if not slightly intimidated by the prospect of collaboration, simply because, as a writer, it is new to me.

SW: Mothering is a construction, that has been widely discussed by Elisabeth Badinter, the French philosopher who wrote on motherly love. Emotions and intimacy seem to be constructed in general. How does this affect the postion of the father in DADDY?

TJ: Perhaps it emphasizes that large part of the play wherein the father is absent. It reinforces the absent father’s haunting of the world that the play takes place in.

SW: The Christian religion is a father religion and defines the father as absent. How productive is the presence of the father in DADDY?

TJ: The “daddy” of the title is an 11-year-old boy, who, fatherless, becomes a father himself – and then, by a certain turn of events, doesn’t. The other father, I suppose, is Preacher Creacher, the leader of the cult, who instills himself as a fake father over others – yet his sincerity is ambivalent throughout. So the figure of the father goes through many cycles of presence and absence throughout the course of the play. In this sense, I’d say it’s quite productive – we’re gonna make a lot more daddies than we are babies.

Ernesto Ortiz @ Golden Parachutes

by Travis Jeppesen on May 30, 2009

The border, as both physical reality and philosophical entity, forms the backdrop of the paintings Ernesto Ortiz is working on for his first solo exhibition, opening on May 23rd at Golden Parachutes in Berlin. Indeed, it could be said that the U.S.-Mexican border is one of the rare places where the supposed abstractions of philosophy become manifested in physical form. At a time when relations between the two nations are at a tense impasse, it seems highly appropriate that the artist, born in the United States of Mexican heritage, would choose this moment to reflect on the self-created American myth of “the other.”

Read the rest of the essay at WhiteHot Magazine of Contemporary Art.

I’ve Written a Letter to Daddy by Bruce LaBruce

by Travis Jeppesen on May 28, 2009

As many of you know, my first play, Daddy, will be produced in June at the HAU Theater in Berlin. Bruce LaBruce recently wrote this nice essay on the play, which I thought I’d post here. Tickets to Daddy can be ordered directly from the HAU website.

Finally, the voice of a new generation has emerged. Took you long enough. If Hubert Selby, Jr., William Burroughs, Anthony Burgess, J.G. Ballard, and Dennis Cooper had a circle jerk, commingling all their spermatozoa into one primeval goo, then squeezed it into a turkey baster and presented it to Flannery O’Connor, imploring her to impregnate herself with its contents, nine months later out might stroll one Travis Jeppesen, the author of a new play called Daddy. It’s an ingenious little dramatic concoction involving all the modern pop shibboleths worth caring about: Marshall Applewhite and his Heaven’s Gate suicide cult; child rapist/bearer schoolteacher Mary Kay Letourneau and her boy groom; alien abduction, rape, and hybridization; shrapnel-riddled Iraqi war veterans banished to Guantanamo Bay. They’re all here, the thousand unnatural shocks that the new flesh is heir to, all in the imposing form of Daddy.

Born in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, raised in Charlotte, North Carolina, and educated in New York City (mentored, significantly, by author Bruce Benderson), Mr. Jeppesen made the wise decision, at a tender age, to escape the rotting new empire for the floppy, folded flesh of Old Europe, specifically the aged whores Prague and Berlin, who took him to their ample, drooping bosoms, heavy with history, and let him drink from the milk of human corruption. His literary ambitions stoked, he began to edit a literary journal called Blatt and wrote his saucy first novel, Victims. Now he assaults and insults us with a play that combines the reckless New Age dyslexia of America with the cantankerous, syphilitic wisdom of Europe, the “managerial class of the 21st Century”, as he astutely terms it. In fact, Mr. Jeppesen’s political analysis of the new world order is worthy of an extended quotation:

“The European, though she may gradually become extinct, still forms the managerial class of the 21st century. Primitive peoples who are unable to manage will always rely on the European’s bureaucratic expertise as the ultimate wellspring of material salvation. The American, who may be driven impotent by all the saturated fat in his diet, but can always gorge himself to death on the righteousness of his imperialist ambitions, will continue to view himself as Leader regardless of his flaccidity. It is much like the ceaseless competition between evolution and devolution: The American has God on his side, while the European’s salvation lies in her very godlessness. All her icons have been transformed into very profitable tourist attractions, easily recognizable signs offer reassurance in the only language that matters. It is not possible to get lost in the streets of European cities anymore – McDonald’s is never far. By feasting on our likenesses, we destroy all recognizable concepts of the other, put it safely in the realm of images, which is meant to be synonymous with illusion.”

But wait, before you get your knickers in a Gordian knot, please be aware that this polemic is delivered in Daddy not by some priggish professor, but by the character of Missus Pringles, a single white mother struggling to become an international theatrical celebrity even if it means abandoning her only son whose father was tragically eaten by walruses! In this play, astute political analysis is conveyed through broad neo-Ortonian farce, not bland didacticism. In fact, the conscience of the play, a stacked black Banji girl from the projects named Derika Taleisha Latorrah Alexander, raises American race relations to new heights with her homespun homilies, to wit: “Everybody got a Daddy. You either got one or you is one.” And when you add pornography, Judge Judy, Evangelical preaching, and the art of speaking of tongues to the mix, not to mention a cult of women whose members are each called Belinda and a superior alien race that speaks with its own distinctive vocabulary, it can be safely said that there is never a dull moment in Daddy.

Bruce LaBruce

Reading on Thursday, Berlin

by Travis Jeppesen on May 26, 2009

‘Movin’ on with VERSES’

A new evening of poetry & spoken word

Thursday 28th MAY 2009 9pm start

@ Sin Club, Schönleinstrasse 6, Kreuz-köln

Hosted by lady gaby with special guests:

1. Travis Jeppesen is an American poet/writer editor of the cultural magazine Blatt, author of Victims and Poems I wrote while watching TV. His latest novel, Wolf at the Door confronts fear and devastation, destruction and creation and the decay of both spirit and body with a blend of black humour. He will read from poems from an upcoming & soon to be published anthology.

2. Experimental Video by artist Teresa Lunau..

2. Jennifer Nelson is an American art historian and writer who has sometimes published really charming juvenalia in magazines like Fence, the Denver Quarterly, LUNGFULL!, can we have our ball back?, and others. She wants to stay in Berlin, where she has been conducting dissertation research, and is sad to have to leave.

3. Live music from Australia, Melbourne the group: BRILLIG

Curiously dark in the tradition of Lewis Carroll, both lyrically and in mannerism, Brillig possess an odd quality that imbues adept story-telling with days-gone-by poetic flair.

Jack Goldstein @ Daniel Buchholz Gallery, Berlin

by Travis Jeppesen on May 26, 2009

The story of Jack Goldstein is one of the saddest in recent art history. Throughout much of his career, Goldstein struggled with fame – both his own and that of the artists who rose to prominence alongside him in the now-legendary Pictures exhibition of 1977 – as well as the crude dictates of market forces that came to define the subsequent years. As the decade of hype wrapped up, Goldstein quit New York and the art world altogether to live in isolation in the deserts of California. Throughout the ‘90s, the artist apparently produced next to nothing. He re-surfaced briefly in the early aughts for a brief flicker of a comeback. Goldstein himself, however, was no longer game. He took his own life early in 2003.

The current exhibition brings together a representative sampling of Goldstein’s work in several media – namely film, sculptural objects, and paintings.

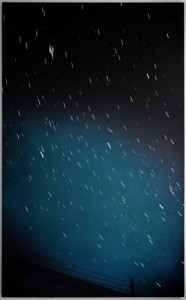

While it is the film work that has proven most influential among today’s artists – and the five here, refreshingly projected in the original 16mm format, include some of his more representative efforts – it’s unfortunate that Goldstein’s paintings never got their proper due. When his original canvases weren’t dismissed outright as bowing to market demand in the post-Pictures frenzy (the logic being that a video artist ought to remain a video artist), they were “explained” away under a barrage of barely legible prose penned by critics who had inhaled one too many copies of Semiotext(e) paperbacks without allowing time for digestion. That the paintings – depicting lightning and electrical storms, volcanic flare-ups, and hallucinatory nuclear meltdown, typically framed vertically or horizontally with bars of color – were actually quite spectacular in their photo-sharp depiction of nature’s fierce tantrums, seems to have been overlooked.

One never knows who the enemy is in Goldstein’s world – whether it be nature or the technology we have created to “protect” us against our cultural enemies. (Remember: Goldstein was a child of the paranoid ‘50s.) In an untitled canvas from 1982, meteorites storm down from an electric green sky on to a barbed wire fence – though the meteorites could just as well be beams in some nightmare Soviet Star Wars episode conjured by Ronald Reagan, the fence ensuring our imprisonment in the apocalyptic death fantasy. An untitled red painting from the same year is even more doomsdayish, portraying the black silhouette of an urban skyline, at the center of which stands a tower emitting spirals of electric light.

Goldstein once said that it was art’s duty to explore and occupy “danger zones.” While his paintings brought him closer to all that was potentially lethal in nature and humanity, the exhibition ultimately sounds a regretful note when one realizes the impersonality of Goldstein’s project. Had Goldstein chosen to confront and work with his own danger zones rather than evade them, it’s quite possible that we might be looking at so much more from this ever fascinating artist.

Galerie Daniel Buchholz

Fasanenstr. 30

May 1 – June 13