Roman Holiday: A Travel Journal

by Travis Jeppesen on June 16, 2008

Roman Holiday: A Travel Journal

ARRIVAL

Thought I could keep everything intact – a towel? That won’t absorb my lust. I am holding onto you anyway. Fantasize a way of life like on TV. Wait, that’s not fantasy. Two ducks doing their mating dance outside my window, reminds me that I’m still in love with love. Not everything has been lost, it now seems. We’re inside now. Moving to a backwards beat, the sacred motion. What goes through us so casually can never truly belong. The sensation greater than that, and we’re still moving. Maybe when I finish up my travels across time. It will feel much better anyway, a live caged animal. Remembering the forest I went to as a child, and how come a spider never bit me, a rattlesnake. What I was too cruel to know was experience itself. The magnitude crept up on me. I was a teenage toy, inside myself with laughter. The symbol that threw itself at my wanking jar. The vibrancy inside her. Not all such experiences are wasted. We forget what they teach us at times, that therapeutic cryptosy that dares to unenlighten. I am a zoo for my fears. My friends number in the unbecoming.

A VISIT TO THE JOHN KEATS HOUSE

Lift not the painted veil which those who live

Call Life: though unreal shapes be pictured there,

And it but mimic all we would believe

With colours idly spread, — behind, lurk Fear

And Hope, twin Destinies; who ever weave

Their shadows, o’er the chasm, sightless and drear.

I knew one who had lifted it – he sought,

For his lost heart was tender, things to love,

But found them not, alas! nor was there aught

The world contains, the which he could approve.

Through the unheeding many he did move,

A splendour among shadows, a bright blot

Upon this gloomy scene, a Spirit that strove

For truth, and like the Preacher found it not.

– Percy Bysshe Shelley

ACCOMMODATION

Impressions of Italy. What I will start with, upon my arrival, we were invited to the flat of the neighbor of the guy we were to rent our flat from. He offered us beer, then a glass of Sicilian red. What I noticed in his living room was paintings paintings – mainly small paintings – paintings covering every surface of wall. When I went to the Vatican Museums for the first time, I understood why. The Romans go for that sort of excess. They enjoy watching it mount. When you go into the Pinakotheka, the pictures begin small, then the canvases grow larger as you go along.

I forgot how boring it was, to be an American. Not that you’re ever totally detached. Just wander into the touristy part of town, hear their voices. Don’t talk until it’s all over.

Narrow it down, fucker. You’re dissatisfied, seeing it cloying its way past you. Once you will be destroyed, then lash out, start making ridiculous threats against the world. Unrestrained, you will break apart in the face of all reason. The priests and nuns afraid to masturbate incur god’s wrath. Spiderfucked by orgy fantasies and back alley abortions that grow up to grow hairs.

When I go outside, out on to the balcony, nightchills bite my breath, my willis stands on end. Could I be everything I am denying? Congratulations! You make this into a swell date. It won’t be swollen, the times you are following.

CORREGGIO AT VILLA BORGHESE

God pissing on a larger stone apparatus. The Virgin and her baby getting educated.

GIORGIO DE CHIRICO AT MUSEO CARLO BILOTTI

This billionaire died and left his art collection to the city of Rome. So then why does the public have to pay money to see it? Well, I guess he wasn’t that generous.

Most of the museum was closed off the day we went to see it. In fact, the only thing we really got to see was his collection of de Chiricos. Combined with the smaller collection of works at the National Museum of Modern Art, you get a good survey of the painter’s devolution from metaphysical visionary to purveyor of kitsch classicism. A black and white painting at Bilotti, Archeologi Misteriosi – Manichini – Il giorno e la notte (1926), gives us the painter at his finest, fusing the human body with cities ancient and modern.

AESTHETIC OBSERVATIONS

Sugar in my clothes, call the police and get me out of here. I have married a second savior for sure. Are you willing to get the hell out of the ass of my looseness? No memento is moving. If only I could satisfy the toss of dreams, catch myself out at the superiority I once feigned to enjoy. Before I fell apart, my hands were truly made of leather. I shared your faith with my armpit; a belch in the kitchen carries me away. You are my darling, you are my ashtray. You are spreading baby rumors around the neighborhood. I never had a baby on your face, I am sorry. Are you a woman or a suntan? A minute consideration of causality. Seagull’s presence too far inland, reminds me of my own species. Then I was a survivor. Set me up for going broke – everything that is to be achieved here is now crying. Superb priest’s ornamentation rots out the gaybar. It smells like feet everywhere I go.

=

Woke up this morning with a brain in my mouth. Didn’t know what I was doing; called Laura. Invigorated with precision, started to do some math. Tampered out at arithmetic’s deluge. Wish I was sweet; wish I could produce my own tempo. The dream always works diagonally. Shepherd comes in the picture to drown out the sheep’s opposition.

A STROLL DOWN VIA MARGUTTA

Around the corner from the Spanish Steps, Via Margutta has traditionally been the Roman street for artists. Fellini lived here until his death, and the street is still filled with galleries. I was surprised by the high quality of work I saw. Unlike the comparable Auguststrasse stretch in Berlin, where you have to wade through a lot of murkiness in order to recover the gems, Rome seems intent on proving to the world that great art isn’t merely a thing of the past.

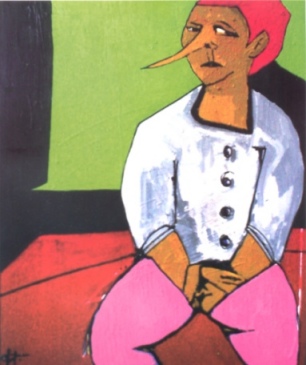

The youngest artist I saw, Giuseppe Tesoriere, was born in 1981. He already has a unique style developed, which works for me, although it clearly won’t be to everyone’s liking. An eccentric colorist, Tesoriere offers acrylic paintings of distorted human figures rendered in sharp lines and pointy angles in his exhibition at Monogramma. The paintings are cartoonish, yet also quite sophisticated.

One day, the history of Abstract Expressionism will have to be re-written in order to include a slew of Italian artists who, seemingly unbeknownst to their American counterparts, made an energetic and lasting contribution to the 20th century’s most important painting movement. Chief among these was Emilio Vedova, subject of a retrospective at Campaiola. Most of the paintings are on medium-sized canvases – usually around 80 x 60 cm – and contain large brushstrokes. In some cases, such as the wound-like (red/purple/black) untitled painting from 1968, scratches are made in the paint using a stick-like instrument, etching artificial avenues in the chaos of the artist’s anti-world. In an untitled from 1960, thick black brushstrokes evoke the work of Franz Kline, while slighter vertical slithers seem to emerge stark-like as figures, calling to mind the drawings in Cy Twombly’s North African notebooks – particularly in the contrast of the black dashes on gold background.

The quality that I admire about Vedova – and Italian painters, in general, stretching back throughout the centuries – is that size is never confused with scale. That means that you can have a monumental picture that is actually physically small. Viewing several of Caravaggio’s paintings for the first time at Villa Borghese, I was surprised at how relatively small the canvas was compared to the image I had in my mind based on viewing reproductions. This does not detract from the overall painting – if anything, it fosters greater concentration on the image itself, rather than overwhelming us. Countless American artists could learn a lot in Rome, namely, those responsible for all of the bad art produced in recent years under the “bigger is better” banner.

To draw out some further comparisons: Where Berliners value coolness, Romans favor eccentricity. This is why the works of a painter like Odd Nerdrum, currently on at First Gallery, look so amazingly good in Rome, whereas in Berlin, they would likely be met with snarls of derision. Nerdrum has made a career of steadfastly following the tradition of Rembrandt and seemingly ignoring everything Modern. I say “seemingly,” because the Modernists relied on the past in “making it new,” and in this respect, Nerdrum is more modern than the Modern. The surfaces of his paintings of floating figures gleam; it looks as though the paint is still wet. A work like Burning is endemic of Nerdrum’s latest concerns; a single nude figure floats face down in an earthy sea. A new form of classical beauty, almost unbearable, and very Odd indeed. (On a sidenote, curator Marco Di Capua’s “Dark Limbo” is the best in the fledgling Catalog Essay pseudo-genre I can remember reading. Fuck theory – let’s have more poetry!)

ON THE GAY BEACH

I got sunburned.

THE CHURCH OF DIEGO TOLOMELLI

Of all the churches I visited in Rome, this one was undoubtedly my favorite. Diego Tolomelli is the only artist in the world making homoerotic stained glass. I was fortunate enough to be invited to his studio while he was in the process of completing a Saint Sebastian. Tolomelli’s style is decidedly mod prim; notice the thick black lines in his Sebastian below, the sexy tattoos. With the recent revival of interest in the Gothic across all fields of cultural activity, I think it’s only a matter of time before Tolomelli takes over the world.

ANCIENT VS. MODERN

When does tradition upend itself? Is finality’s refuge a used car lot? Can’t I figure out what I’m pretending to be when I have a self and little else? I fucking struggle to get it all out, then I’m dead and I can’t write no more. Imagistic shadow. Horizon’s grapefruit. Over the end and then I’m free. Muscular endgame triumphant. We are there and then – both simultaneously and at once. Times alone lead to artificial superiority standards. The layman’s duck cloud and what species means, drown the names.

To be, in rapid felicity, a white light fading. Animal mother comes out of the woodwork to feed a cloud. We were within the days, within the storm. Trying to get it mottled down into forthrightness. What can’t be controlled can at least be fostered. Is it too much to birth the moon? Sure, I scare myself sometimes. Too much gravity is a terrible thing to be forced to confront. I am a satellite on top of the moon. Sad wonder is all the same then – we are drugless anchovies wanting. I am writing for the, into the future. I am writing the future.

You’ll Know What to Do: Vaginal Davis Guides Us into Summer

by Travis Jeppesen on May 26, 2008

The maverick terrorist drag artist Vaginal Davis was recently enlisted by the Berlin art academy at Weissensee to submit a select group of students to a sort of week-long avant-garde boot camp, the result of which was a one-off performance, You’ll Know What to Do, which took place last Friday, May 23rd, at the Raumerweiterungshalle, a venue that has been described as “a mobile, telescopic, extendable container,” and is situated in the back lot of the former Kindl brewery. The place looks a bit like a circus sideshow tent, and the freak show atmosphere pervaded from the moment I arrived on Friday until the sun had completely disappeared. Of course, it was a Berlin-style freak show, which meant that a well-stocked makeshift bar in the parking lot was already well on its way to being depleted by the time I got there.

As the drinking festivities bled into performance activities, we were invited to submit to one of three hypnosis booths protruding from the Halle: phallic hypnosis, clitoral hypnosis, and nasal hypnosis. I ended up at the first of the three – big surprise there. I was given the power of “posing.” I’m sure it still hasn’t worn off.

After being properly hypnotized, you were allowed to go inside the Halle. The entire room was bathed in a fleshy red light. Ms. Davis herself stood near the rear, chanting a litany of sexually transmitted diseases, while a slither of strange noises erupted from a couple of musicians. As the evening clusterfuckery progressed, it began to feel as though we had been engulfed in the re-enactment of a Kenneth Anger film. A mummy rose from the dead, picked up a bass guitar, began to play. Everything started to get very noisy, and pretty soon, we were witness to a human assemblage – caked in duct tape with phallic protrusions extending – falling into a single, elevated pile as sand was flung in every direction. The energy level sky high, the performance then morphed effortlessly into a dance party.

There was something decidedly quixotic about the evening that kept both performers and audience pleasantly on edge, and no one really wanted it to end. The crowd stuck around – swaying, talking, kissing, dancing, and gossiping – for several hours after the fact, when those who remained stumbled a few blocks to a late night fried chicken place that only the divine Miss Davis seemed to know about.

You’ll Know What to Do was actually the second of a three-evening row of Vaginal Davis events. The previous night at West Germany, a semi-legal club for experimental rock music in Kreuzberg, Davis turned in a riotous set accompanied by Johnny Blue, alongside Kill Rock Stars recording artists the New Bloods. She decided to keep it short and sweet – a bit disappointing for those of us expecting a full set, but potent enough to remind us of the raw energy she used to enliven such music projects as P.M.E. and Black Fag in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

The Vaginal Davis weekend came to a close with her monthly film/performance event, Rising Stars, Falling Stars, at the Kino Arsenale. This evening’s entry showcased The Perils of Pauline, one of the first cinematic serials, from 1913-1914. After Davis’s hilarious silent starlet introduction, brothers Tim and Johnny Blue launched into their musical accompaniment for the evening – an interpretive hodge-podge consisting of clever samples, affective noise played on non-instruments, drums and strings. Overall, the Blues’ clever riffing on Pauline’s perils brought a sophisticated 21st century conception of the sublime to bear on the classic serial, making for a spectacular evening of synaesthetic bliss – after which, of course, the wine continued to flow…

Berlin is, among other things, the most manic of cities. It is bitterly cold and gray throughout most of the year, and the vibe on the street seems to match this perennial depression. Sure, people carry on drinking and carousing behind closed doors, but when walking from one bar to the next, you don’t really get the impression that people are enjoying themselves. They’re too stuck in that melancholic introspection that has come to signify Central European dismality to the rest of the world, and you don’t get the impression that anyone really has much of a desire to climb outside of this bitter pit of black bile.

That all changes as soon as winter gives way into spring. By the time summer rolls around, it is as though an entire new populace has moved in – the streets are crowded with sidewalk cafés filled with half-nude bodies from dawn to dusk, the parks overflow with flesh and greenery, and it suddenly feels as though no one living here is in a hurry to get anywhere. Berlin really only comes alive beneath the sunshine, and since its denizens only get to bask in it maybe two to three months out of the year, they become pagan worshippers of both shrubbery and concrete. The scent of lust pervades the air, the pursuit of hedonistic pleasure becomes everyone’s number one goal, anything resembling work in the slightest is scoffed at and put off until the sun’s energy dies down and the arrival of autumn makes its grim recognition felt like the onslaught of a particularly harsh comedown.

A pagan goddess of bewildering talent, conjurer of the indefinable, constant deflator of establishment principles, muse of the millions: If any one artist could be said to encapsulate the spirit of Berlin at the present moment, it is Vaginal Davis. Summer might not officially begin for nearly a month, but those of us fortunate enough to have sampled Davis’s bacchanalian orchestrations in the past week share a common secret: The virginal spring is over, the Vaginal summer has begun.

Jarman, Julien, Wittgenstein, Martians

by Travis Jeppesen on May 22, 2008

Of all the possible mediums he could have chosen, it is somehow curious that Derek Jarman decided to become a filmmaker. He didn’t just do film, of course, but it is for his films that he is best known. Perhaps you get the feeling, when watching some of these movies, that they should have been plays. Perhaps this is due to the fact that the films are not really films at all, and their theatrical energy is the immediate feature that engulfs you, that allows you to withstand their occasional lapse into preachiness.

A recent trip to London led me to re-assess my thoughts on Jarman. I was never the biggest fan of his films, but something about his style nevertheless captivated me. By the time I saw most of them in the late 1990s, their political content was already starting to feel quaint – the product of a former era, which is sad considering the fact that he was one of the few artists with AIDS brave enough to take a stand and address his illness in public when such matters were still considered taboo. At the same time, it no longer felt like one was fighting a battle by being queer; if anything, the battle was now against the commoditization of gay lifestyle, a subject that had been brought to task by a new generation of gay filmmakers led by Bruce LaBruce.

The exhibition I saw at London’s Serpentine Gallery attempted to assert Jarman’s historical relevance. Organized by the artist Isaac Julien, it featured Julien’s recently completed documentary on Jarman; a screening of Jarman’s final film Blue, which features a blue screen and the voice of the filmmaker, speaking intimately to his audience; several of his rarely seen super 8 films; and a small selection of his paintings.

The exhibition is closed now, but the work, of course, will live on, in its own small way. What I mean by this is that Jarman’s films do not play well on the small screen – they really need to be watched in a cinema in order to gauge their peculiar theatricality. It is probably the theatricality itself – particularly in films like Jubilee, Jarman’s clunky, heavy-handed vision of a post-apocalyptic England populated by punks – that makes these movies feel so dated. In her book Aliens and Anorexia, Chris Kraus writes that calling someone’s work “theatrical” is about the worst insult you can give an artist these days; she then goes on to show us the implicit value in theatricality, the heightening of the emotions over the self-conscious “coolness” that, now that it’s been about forty years since Warhol did anything important, is starting to feel a bit cliché, to put it mildly. When applied to Derek Jarman’s oeuvre, Kraus makes a convincing argument for re-considering the maverick filmmaker’s work.

Julien’s Derek, on the other hand, makes no real argument for the work’s ongoing importance, focused as it is on Jarman himself. I find it rather odd that Julien, who is an artist, would make a documentary that doesn’t bother engaging in aesthetic questions regarding Jarman’s work. Given Jarman’s politicized existence, his personality is already better known than his films; Derek merely tells us, once again, that Jarman should be canonized. Well, there’s no need – everyone already knows he’s a saint.

More helpful to me than the exhibition was my subsequent discovery of Wittgenstein, one of Jarman’s final films, on DVD. I’d wanted to see this film for years, but found that it was tremendously difficult to track down. The film was Jarman’s last before Blue, and is rarely discussed. When it is mentioned, it is mostly in derogatory terms, inferring that the film was considered by most to be a failure. I think it’s quite the opposite – it is perhaps even Jarman’s masterpiece.

I don’t think it’s a random coincidence that Jarman chose the elusive philosopher as one of his final subjects. Wittgenstein evolved a sort of performative philosophy that was unique in the history of the discipline. He asked questions that you technically were not supposed to ask, he brought common sense thinking back into a realm from which it had long been excluded, and he used his imagination to design scenarios and conceptualize his thoughts into patterns, the universal applicability of which he would rigorously test. He re-wrote his work over and over, discarding his thoughts almost as fast as they came to him, only publishing one completed book in the course of his lifetime. He came to see philosophy “as a by-product of misunderstanding language.”

Jarman understood Wittgenstein, a figure whose philosophy and personality seemed interwoven into one complex whole that very few managed to unravel. In one scene, Jarman has a Martian interrogate Wittgenstein as a child about philosophers. The dialogue that ensues is a witty take on the limits of language, one of Wittgenstein’s central problems.

Like Wittgenstein, Jarman had his own style that seemingly came out of nowhere. In The Angelic Conversation, disconnected sound and image form a sort of collage wherein elements of camp and classicism merge. The “story” seems to have to do with two beautiful men finding themselves – and each other – in a journey traversing “forbidden” desire; when the two men wrestle, it is almost impossible for us to tell if they are fighting or fucking. A grinding soundtrack by Coil feeds into the barrage of lo-fi images spread across the screen, and a selection of fourteen sonnets by Shakespeare is read by a female voice. The film coheres not merely on a cerebral level, but on an emotional one, as well.

Not all of Jarman’s films work so well, but it doesn’t matter. His peculiar concern with philosophy, sexuality, the apocalypse, classicism, and modernism – not to mention his fierce political commitment, a sensitive and personal response to the West’s self-destruction – must be re-visited every now and then in order to see their importance.

Derek Jarman’s Wittgenstein

by Travis Jeppesen on May 20, 2008

Alien Insurrection: A Note on Theory

by Travis Jeppesen on May 20, 2008

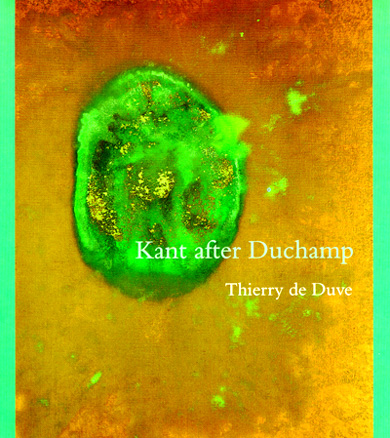

I’ve been reading off and on this since shortly after I attended the Martian Museum of Terrestrial Art exhibition in London. I was intrigued by the title, so I picked it up. I have to say, I’m finding it quite dull. Theory seems to do little more than ruin one’s experience of a work of art. The older I get, the less interested I am in walking around with other people’s ideas jumbled in my brain – especially when I look at something – they just get in the way. History seems so much more important. History answers questions that theory can only poke at.

A question to artists: Is theory more important to you than literature (fiction, poetry, etc.)? Why? (Ignoring criticism at the moment, considering it to be a separate field, separate from both “theory” and “literature,” as vaguely designated above. The reason is complicated, and I will attempt to explain it later.)

Rauschenberg: 1925-2008

by Travis Jeppesen on May 20, 2008

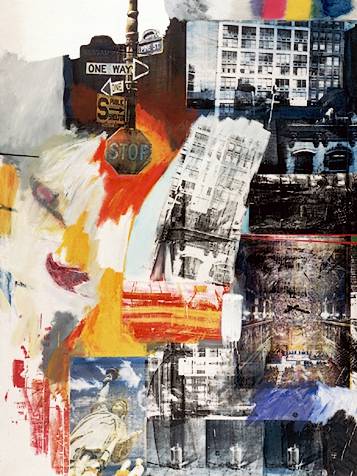

It’s hard not to fall into the trap of thinking about Robert Rauschenberg from a historical perspective. Like two of his lovers, Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly, he is frequently seen as a transitional figure, and perhaps more than the others, he was the artist whose work formed a bridge from the Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s to the Pop Art of the 1960s. By circumstance, he was also the first artist to introduce the enfant terrible notion into the American art world, becoming infamous – if not openly despised by the critical establishment – with his first exhibited works, which no one could make sense of at the time. For many, that struggle continues.

One typically becomes the establishment by resisting it for the vast duration of one’s life. Rauschenberg got “in” early, then went back “out” as soon as he could, living for much of the latter half of his life on an island off the coast of Florida in relative isolation from the rest of the so-called art world. He never really evolved much as an artist – his work either stayed the same or grew less interesting as he got older. He kept making it, though. I haven’t seen enough of the later work to pronounce judgment on it, but perhaps some enterprising institution will throw together a definitive exhibition of the later work, from 1970 up to 2008, to allow the public to decide.

My own relationship to Rauschenberg’s work is so personal that it makes it difficult for me to trust my own judgment. I wasn’t able to start looking at art seriously until 1997, when I moved to New York for college. Wandering through that city’s great permanent collections, Rauschenberg’s combine paintings had a strong impact on my developing sensibility (which some might call an anti-sensibility.) There was something jarring and anti-aesthetical about his work from the 1960s that I most likely related to through punk rock, my sourceless anger. Rauschenberg assumed the role in art that Kathy Acker assumed in literature. I tried – unsuccessfully, of course – to imitate both, because imitation is what you do early on in life when you have yet to find your own way.

As I grew up, traveled, and looked at more art, I began to have severe doubts about my initial estimation of much of Rauschenberg’s work. The problem for many, of course, is the fact that Rauschenberg’s work rarely looks good. I could never wholeheartedly subscribe to a blanket denunciation of his work (such as Jed Perl’s), because some of it does cohere on a visual level. There are a lot of failed experiments out there, but there’s a quality of motion and rhythm in a lot of his larger paintings that I find completely compelling, even when they make me dizzy and nauseous. A lot of his paintings seem like anti-design. In actuality, I think they represent total design – by going back to foundational design principles.

Still, what remains the most disruptive feature of Rauschenberg’s art is its brutal lack of definitionality. He famously quipped that he wanted to erase the artificial barrier separating art from life, and thus became an ambassador of openness – the American equivalent to Joseph Beuys, but with a markedly different way of going about it. Just as he once erased a de Kooning, he might as well have erased himself, because he wanted his art to be viewed by the world as a creation of the world. The world in its comeuppance, its severe vision of things. He started out as a naïve outsider from a provincial nowheresville, and graduated back into the obscurity from whence he came. With Rauschenberg, it is perhaps still too early to assess the true value of his work.

This piece originally appeared in Think Again, Prague’s free city magazine in English.

Color Theory

by Travis Jeppesen on May 10, 2008

Carsten Nicolai

Eigen + Art, Berlin

Through June 28th, 2008

The day was a pinkish orange thing, and as I entered the gallery, the orange overwhelmed the pink in a way that was unbearable – especially the heat. It is generated by a large neon wall that reflects nothing – just the scent of its own burning. Surrounded by three panels of yellow – one on the left, two on the right – unilluminated. Four silver rocklike formations on a table in front. They reflect the light and energy of the neon, perhaps even radiate with a heat of their own. You suddenly realize that the heat is coming from above, not just in front of you. You look up and nearly go blind – four mega-watt bulbs burn your eyes out. You can’t see what other purposes they would serve – the light coming from the orange is bright enough – so they must have been placed there on purpose.

The exhibition is called “Tired Light.” It has to do with a theory that fascinates the artist, a theory that has it that light loses energy when it travels far distances – hence, tired light. But the light in the gallery is not tired. It is right in front of you. The tired light theory was later abandoned. The space-time continuum became more important. Some say it still is.

If you stare long enough into the orange – if your eyes can handle it – you start to see wavy lines. The orange wall is comprised of three rectangular panels, all equal in height and width. The yellows are much smaller. Where the orange is harsh, the yellow is absorbing. The silver balls reflect. So: protrusion, absorption, reflection. A sensate language lacking a vocabulary. This is not a necessity that burns. It is a heat whose source can immediately be discerned.

Climbing the Anal Staircase: The Art of No Bra

by Travis Jeppesen on May 4, 2008

I.

They say No Bra is all tits and wonder, but they’re wrong. There’s also a lot of cock, and even some fake mustache. This isn’t music for the masses; it’s music that makes fun of the masses – or at least that quotient of the masses that imagines it constitutes an elite.

Susanne Oberbeck dreams of fags and slags, then writes songs about those dreams. She’s singing to herself; the homeless guy on the street. She makes up her own rhythms rather than morphing her madness into someone else’s. There is no other music like this. There’s no spite or cynicism in the stories she tells about the people around her, the people in her dreams. Just a curiosity, which is a natural curiosity; it is rooted in an awareness that people are unknowable, that no matter how close you get to another person, they will always remain a stranger. At a time when electronic music has devolved into fashion and most of its practitioners are visionless victims of pathetic trends, No Bra inserts something closer to the grit of realism into its sound. No Bra doesn’t seem to care if you dance or not. This is a music that isn’t necessarily social, although it can be. It’s an introspective kind of music, introspective and personal. It mumbles and it beeps. Yet it remains whorish and singular and tough to digest.

Oberbeck is fascinated with the illusion of gender – an illusion that, in its systematic guise, has been transmitted throughout the holes and hollows of history, bringing us into the now. She questions this weirdness, and is thus viewed as weird herself. She understands that what can’t be readily understood gets people’s attention. This is why No Bra never feels the need to declaim anything musically; it is rather presented as a form of being – something we’d much rather experience, anyway, as long as that experience is visceral and transitory.

This leads us into the threat of violence that so much of this is predicated upon. No Bra’s characters go to the gay sauna, get their hearts and necks broken. This makes sense; there are many types of pain, why should the pop song only focus on one?

“You make me feel like a woman – You make me feel DEAD.”

II.

Why don’t I chop my own cock off and give it to you as a present (i.e. as a present absence)? Maybe you’d be able to discover a use for it that I’d never, it currently being in my possession, if you can call it that when it’s up someone else’s ass, when I’m literally attempting to invade something, someone I can never comprehend. What is my cock doing while I’m sitting here writing this. Is it asleep. Polka-dot boxers. My first pair. I don’t own them anymore, I don’t remember what happened to them. Chairs on the TV, and when we go by the river at night, are the lights contained inside it? Submerged? I am starting to think there are answers. Answers that make sense. As though we lived in such a world. When the lights dim, does the Actual start to appear? My father was a teenager once. I didn’t know him then. Should I be angry with him because every time he jerked off, it meant I could’ve been born sooner? No, for what if I’d have cancer now, as a different being. I call certain people up in my mind, remember to tell them things it may be too late to be saying. Instead all morphs into shadow. We begin to block out the circumstances. It shows great concision. Those aspects of ourselves we pour so much psychic energy into ignoring, the hopeful result to be that others won’t notice them. Those others become fixtures in our thought landscapes. A nebulous guide. The fields generate their own sadness. You don’t need to lie to yourself to imagine boiling. You are just taking a picture – yourself in another vein. Or perhaps vain. You solve problems every day, you build an engine. No one else inside. Just the pathetic memory of being there, the substances consumed, the blunders made. The railing meant to keep out the goons – but not their stares.

III.

To allege control over circumstances once seemed worth it.

There is a certain interpretation of loss being proffered here. One that entails a misjudgment, or the positing of misjudgment as a possible alibi. Where exactly in the soul does guilt come to be located?

Pastiche is fucked, so is irony.

A voice is there. It makes you aware.

What do your friends look like. When you begin to destroy your surface. Being dead and alive at once. You fall asleep inside yourself, all external reactions pre-programmed. That sort of sci-fi gayness, retrofuturistic faggotry, assert a nod to this week (month/year)’s whim. Grimness is saturated in the desertion of all principled stances, observational annoyances registered in the gesticulation of a tic. The city with its ridiculous way of talking – the darkness and absurdity in its gross dialects. Don’t judge my detritus; I’ll pretend not to notice yours.

Susanne Oberback by Christophe Chemin

hear me read, see me lick…..

by Travis Jeppesen on May 2, 2008

I read out loud (a slightly edited version of) “What the Witch Doctor Says” at Foyles Bookshop in London.

I eat pussy on Bruce LaBruce’s blog.